Mission 300: Halving the gap in universal access to electricity

Over the past decade, Sub-Saharan Africa has struggled to make meaningful progress in electrifying its population. While the global narrative has been one of steady improvement, the region tells a different story. In 2010, an estimated 585 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa lived without electricity. By 2020, the figure had seen a slight decrease to 581 million—progress in numbers but not in impact. Disturbingly, by 2022, the number climbed again to around 570 million, a stark reminder that population growth and structural barriers continue to outpace electrification efforts. Today, the region accounts for more than 80% of the global population without access to electricity, a disheartening share for a continent with vast renewable energy potential.

Globally, the picture over the last 50 years has been far more optimistic. In 2000, roughly two in 10 people lacked electricity; this number has since dropped to fewer than one in 10, driven largely by aggressive electrification campaigns in nations like China and India. While much of the world celebrates near-universal access to energy, Sub-Saharan Africa remains locked in a struggle against systemic underinvestment, logistical challenges, and a lack of political prioritization. The gap is glaring, and the trend suggests that without urgent, large-scale intervention, electrification in the region will continue to lag well behind the global curve.

Source: OurWorldInData

This is precisely why the region has attracted the creation of initiatives with ambitious goals such as this past January’s Mission 300. On January 27 and 28, 2025, the World Bank and the African Development Bank (AfDB) hosted the Mission 300 Africa Energy Summit in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The event focused on expanding access to electricity to an additional 300 million people in Africa by 2030. The summit focused on the high level approach, and as such narrowed into necessary critical reforms across the continent, securing the necessary financing for this transformation, and fostering the right types of partnerships across the region. It gathered the heads of state from 30 African nations; leaders from development partners such as the World Bank, the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the Rockefeller foundation; and several private sector leaders representing various industries.

History of efforts

While Mission 300 has the right target and presented itself as an innovative groundbreaking platform, it is not the first time leaders have gathered to make significant strides in expanding electrification. This goal of providing electricity to an additional 300 million people by 2030 could actually be considered a step down from the Sustainable Energy For All Initiative which aimed for universal access to modern energy services for all by 2030—this was kickstarted about 15 years ago. It was actually in the beginning of the decade of the 2010’s when the world began putting a lot more focus on the issue. Here’s a short history of similar initiatives since then:

The Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL) Initiative was launched in 2011 by former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, and set a global goal to ensure universal access to modern energy services, double the global rate of energy efficiency improvement, and double the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix by 2030. Although its scope is global, Sub-Saharan Africa is a key focus, with numerous projects aimed at improving energy access and promoting clean energy solutions.

Then in 2013, Power Africa, a U.S. government-led initiative was launched and has worked to add 30,000 MW of electricity generation capacity to Sub-Saharan Africa (This represented about an 18% increase in the continent's capacity back in 2015). This ambitious goal included a combination of large-scale renewable energy projects, natural gas development, and efforts to reduce energy access gaps. Power Africa’s emphasis is on supporting private investment and creating a conducive environment for energy sector reforms.

Initiated by the African Union (AU) and the AfDB, the New Deal on Energy for Africa, launched in 2015, was yet another framework for achieving universal electricity access across the continent by 2030. The initiative aimed to provide an inclusive, sustainable energy future by promoting renewable energy technologies, strengthening the energy sector, and encouraging private sector involvement. It sets clear targets for investment and policy reforms to enable the required expansion.

And most recently, the African Electrification Initiative (AEI) was launched in 2018 as a pragmatic response to accelerate electrification using innovative financing models like results-based financing and output-based aid. Rather than ambitiously aiming to power all 600 million people without electricity, AEI set a more targeted goal: connecting 300 million additional Africans to reliable electricity by 2030—a number that underscores both the magnitude of the challenge and the need for incremental progress.

Mission 300 is essentially the next iteration/evolution of the African Electrification Initiative. Taking on the work that the AEI began and iterating on it with a higher sense of urgency and recommitment to the 2030 target.

Feasibility

However, two decades of effort begs the question: what exactly continues to go wrong despite numerous attempts in addressing Africa's significant gap in electricity access? Furthermore, what distinguishes 2025 from the past 15 to 20 years that might enable us to achieve more progress in the next five years than we have over the previous two decades?

Before exploring these questions, let’s contextualize the magnitude of the goal of expanding access to electricity to 300 million more people in the continent.

SEforALL research from 2018 estimates that annual investments of US$52 billion are needed to reach universal electrification goals. Simultaneously, the level of investment that was tracked that year to the 20 “high-impact” countries representing 76% of electrification needs, racked up to US$30.2 billion. So you could estimate that a total of approximately US$40 billion was being rolled out annually globally to close the gap on electrification; meaning that at least a gap of US$10 billion existed globally at the time.

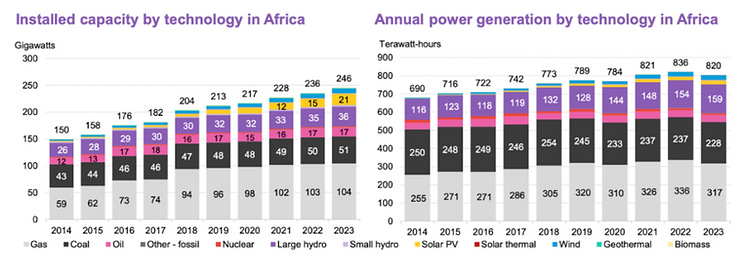

When talking about power capacity, The New Deal on Energy for Africa estimated that achieving universal electricity access meant adding approximately 160 GW of power capacity back in 2015. Essentially doubling the continent’s power capacity at the time to a total of ~330 GW. In 2023, Africa’s total power capacity sat at about 246 GW, which went up from a grand total of 168 GW in 2015. This growth represents average additions of around 9 GW of power every year for the last eight years–which is significant.

Installed capacity, and annual generation in Africa. Source: BloombergNEF

Now to meet the target of 330 GW that is likely needed by 2030 to achieve universal access, Africa needs to install 84 GW of power in five years, or 16.8 GW per year; nearly doubling the rate of additions from 2015 to 2023. But presumably this would represent bringing electricity to 600 million people not 300 million people. So we could cut the target in half to reach the number of 8.4 GW of additions per year in the next five years. Africa is already technically surpassing this target so why is it that the gap in electricity access has not really closed in a significant way?

The problem lies in that the demand for electricity has been consistently outpacing the fast supply.

Africa’s electricity gap persists because population growth consistently outpaces energy investments and capacity expansion. While the continent added about 78 GW of capacity from 2015 to 2023, population growth (over the last decade adding 300 million more people, reaching 1.4 billion in 2023 (UN DESA, 2023)) alone added a demand equivalent to needing at least 150 to 200 GW of new power. This demographic pressure strains not only the ability to generate electricity but also the infrastructure needed to distribute it.

Without massive investments (which are now estimated to require US$120 billion per year) in large-scale renewable projects, grid modernization, and off-grid innovations, the gap will continue to widen, leaving millions without access. Addressing this issue will require coordinated efforts between governments, international organizations, and private investors to bridge financing gaps, deploy faster renewable solutions, and tackle distribution inefficiencies.

In short, Africa’s power challenge is not just about generating electricity—it’s about keeping up with one of the fastest-growing populations in the world.

Outcome of Mission 300

The Mission 300 Africa Energy Summit in Dar es Salaam has one critical mission: deliver reliable and sustainable electricity to 300 million Africans by 2030 and slash the number of people without power in half. It launched a working group by the same name Mission 300, a coordinated effort led by the African Development Bank (AfDB), the World Bank Group, and key international players to finally address Africa’s deepening energy gap.

Key outcomes included the Dar es Salaam Energy Declaration, locking in commitments from African governments to reform power markets and fast-track renewable investments. Twelve nations, from Nigeria and Senegal to Chad and Zambia, rolled out National Energy Compacts—country-specific plans with clear timelines and targets for everything from grid expansion to regulatory fixes. Development finance institutions matched ambition with capital, with commitments totaling over $6 billion, led by the Islamic Development Bank’s $2.65 billion, $1.5 billion from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and major pledges from the OPEC Fund and Agence Française de Développement (SEforALL). However, this $6 billion that was committed in total only represents ~7% of the additional ~US$90 billion that is now needed per year to achieve universal access in the region.

But the summit’s goals face real obstacles. Africa’s population, growing by over 300 million in the past decade, continues to outpace energy capacity growth, creating a moving target. Political instability in regions like the Sahel threatens large-scale infrastructure projects, and private investment, while critical, often focuses on profitable urban markets, leaving rural communities underserved. Without strong regulatory frameworks and targeted government action, large-scale pledges risk producing fragmented outcomes. Overcoming these hurdles requires more than financial commitments—governments must prioritize inclusive planning, accelerated renewable deployment, and stricter accountability mechanisms to ensure Africa’s energy expansion keeps up with its booming population.

Looking to the future

I believe that there is a new trend emerging that may assist in closing the gap between the status quo and this moving target: The decentralization of energy. Technology has reached a point where renewables-powered microgrids are now technologically and economically viable solutions for reaching remote communities in a lot of different parts of the world, and are able to circumvent large capital investments, complex grid planning and politically-charged bureaucratic processes that can get in the way of centralized utilities moving fast enough.

Communities and private organizations can play a more pivotal role in reaching universal access to electricity, and while large centralized efforts such as Mission 300 are still needed for coordination, governments and development organizations need to recognize the potential offered by decentralization and enable these solutions in tandem.

With any luck, if this new technology trend is recognized as a potential boon to the large-scale efforts in closing the electrification gap, we may see Africa finally moving faster and catching up to the moving target that explosive population growth in the continent has created. We will continue monitoring progress for this, arguably one of the world’s most pressing and consistent development issues, and bringing you important context about how decarbonization can help.